Method is/as a layer.

Method is/as a liar.

Method is/as a lawyer.

DOING is/as a method.

«I» is/as a method.

Those sentences popped up in my mind sitting on the balcony, looking on Zurich’s nightlights, after coming back from the team meeting and colloquium, followed by an apéro outside of the campus. It’s a mild night, September 9, 2020. During the colloquium, we discussed Selena’s text More or less? as well as possible layout ideas of her journal-like contribution. It might have inspired me to structure my contribution as interconnected layers of image, text and sound – as if I would edit gathered audio/visual material from field research.

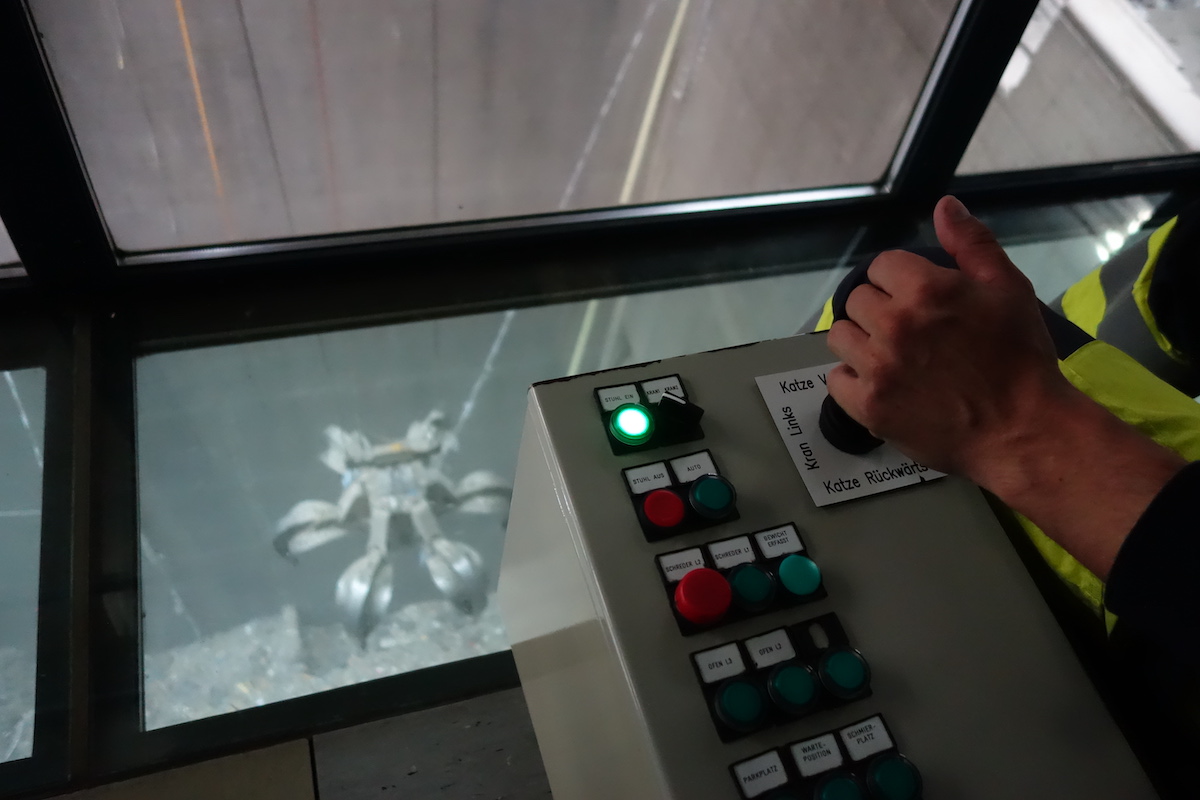

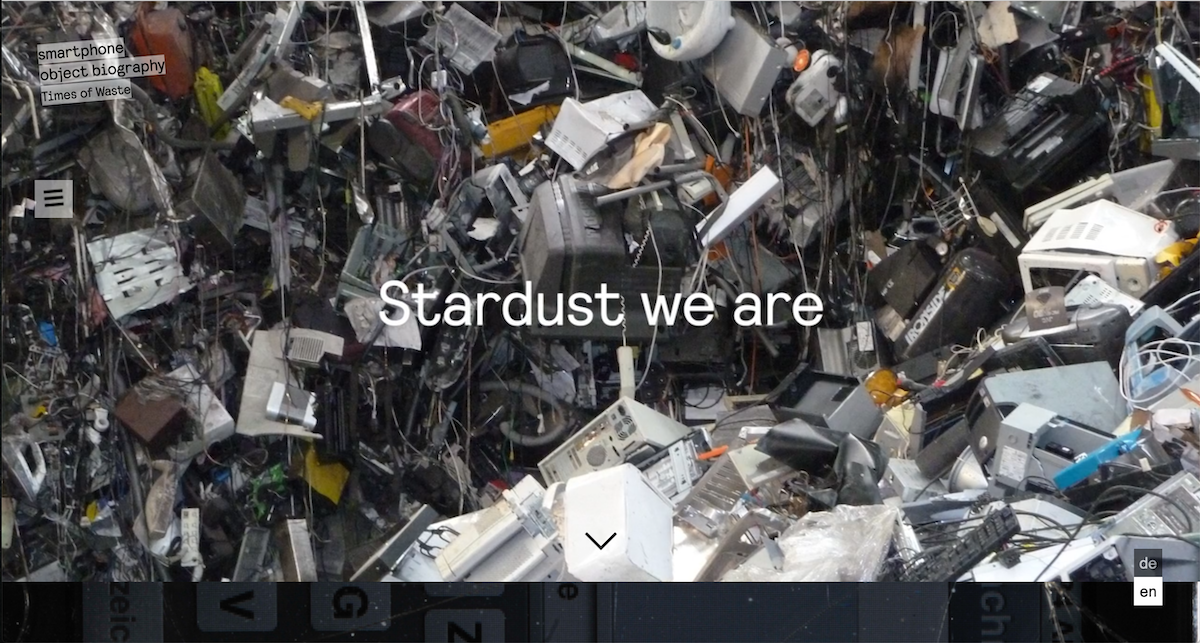

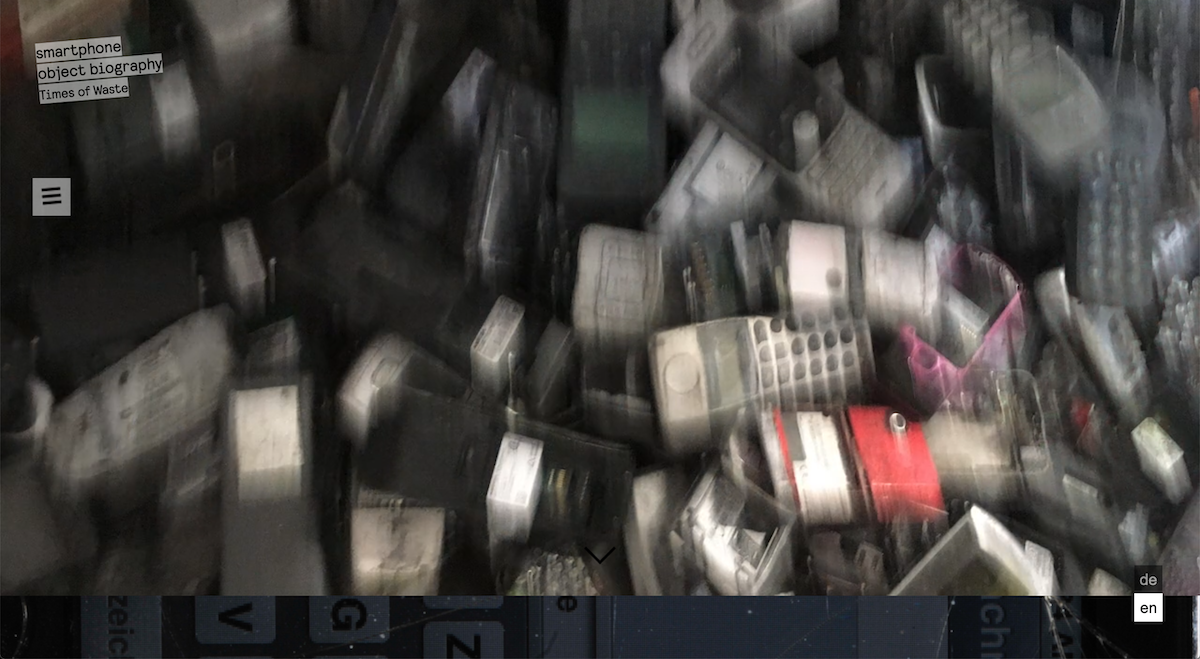

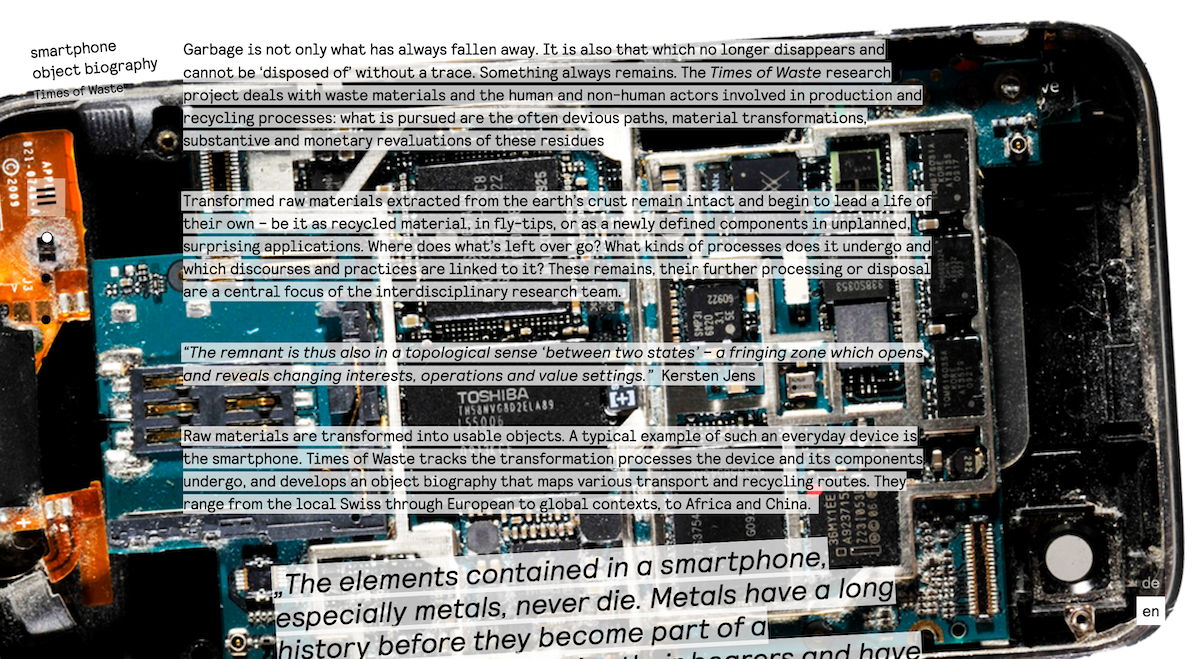

The texts on the left-hand side include general thoughts on the chapter’s topics. The texts on the right-hand side comment on or reflect specific aspects of the research project Times of Waste or feature sources of inspiration and reflection. Image and sound materials were gathered during the project’s field research phase and were part of public presentations (e.g. Times of Waste – The Leftover or the smartphone object biography, an online archive).

This assemblage of text fragments, images and sounds works associatively and aims to open up interspaces for (re-) thinking while receiving.

The first two sentences came as associations. The third because of the sound and rhythm (and probably David Lindley’s song Talk to the Lawyer).

The fourth and fifth sentence joined the line a bit later and form a summary of the first three. They crossed my mind some time ago: In summer 2020, I planned to write an essay on DOING as a qualitative, explorative and performative practice in field research. I intended to experiment with the ‘perspective’ of method as a ‘collaborator’ while talking about modes of collaboration between people, materiality and technology (as research instrument) in our project Times of Waste.

On layering, (re-) ordering, (re-) assembling during processes of montage in research and in reception

One way of working with artistic-scientific research methods can be to combine and synthesize layers of information and media fragments gathered during (field) research. This process might be compared to montage — a manifold technique and aesthetic practice to work with textual, visual or auditive research material. Montage offers the possibility of juxtaposing images and sounds, sensations, information and analytical comments, and to create different layers of perception and reception. These layers of meaning can simultaneously change their sense, break up any fixed order, and create new orders.

Montage is not only a visual or textual method, but also a way of dealing with more-than-human worlds and their ongoing re-creations.

Elements placed next to each other via montage form gaps or fractures which are characterized by instability. This instability connects both elements, but at the same time distinguishes them from each other. These interspaces or gaps challenge the imagination of the spectator during reception and promote different perspectives by destabilizing conclusions.5 Montage is a splintering of pre-established orders, and at the same time it is a reassembling – and «beyond these assemblages, new order may appear»6.

Montage in its extended understanding does not specifically refer to a visual or textual method, but to a «sensibility and mode of engagement with the world»7.

The unstable interspace created by montage may symbolize an opening up for interacting in and with the world and rethinking its circumstances — the possibility of reconfiguring the world we live in. This reconfiguration allows a reassembling, rearrangement or rethinking. It’s a process of «worlding», the need to develop practices for thinking that are not limited to functionality, but instead propose the «possible-but-not-yet», or that which is «not-yet but still open».9

«Montage, mon beau souci.»1

Montage as care. It’s more than a technique. But with the same considerations of «how to care»2 in a more-than-human environment?

Caring is not a human privilege. It allows to integrate diverse points-of-view, topics and debates. Care is an «assemblage of neglected things»3, a web of processes where many agencies, human and non-human, are involved.

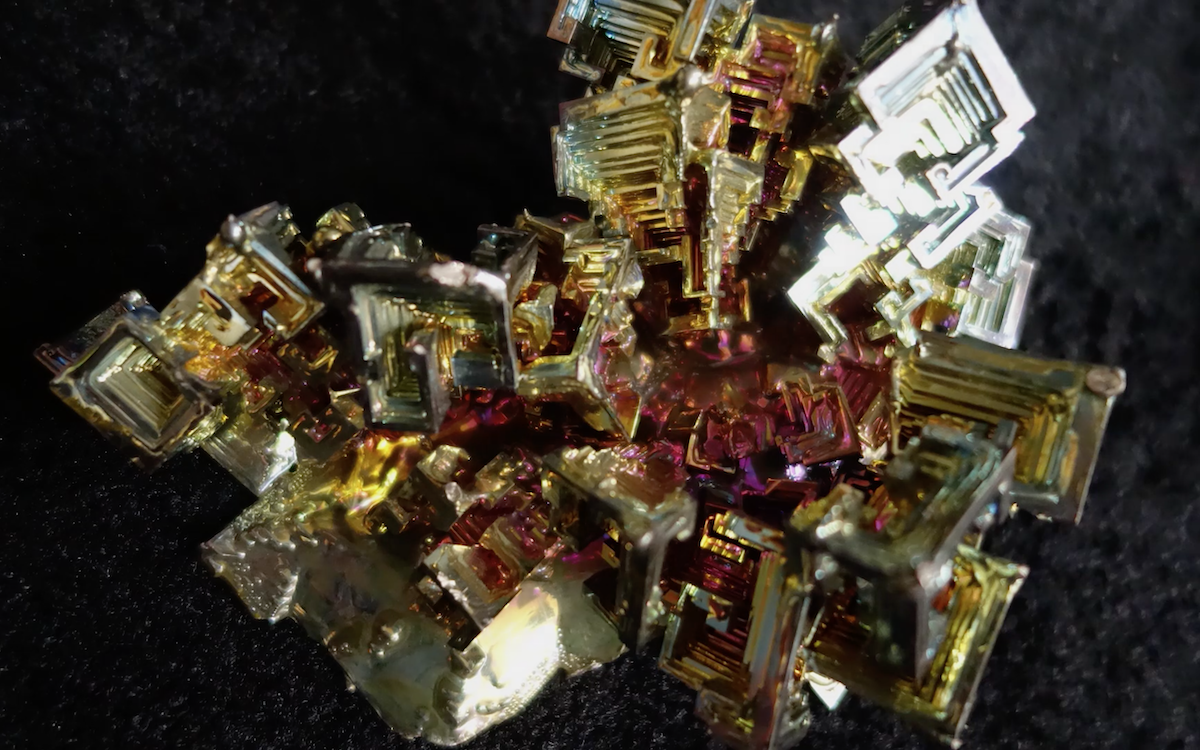

Layers of earth are removed and at the same time leftovers are accumulated, and (most of the) waste is already produced during the mining of raw materials used for the production of devices.

Montage in its narrower sense describes the specific editing work we did with the auditive and visual raw material gathered during the transnational research process in Times of Waste.

We traced a material’s movements through visiting its sites of origin or transformation. The ‘concatenation’4 of the various media fragments allowed us to put the routes and transformation processes of objects and materials in an overall context. The programming of the smartphone object biography made for the basis to map these processes — from local to global contexts — for the interested public. The decentralized character of this multi-sited8 archive allows to combine and juxtapose, to unveil transnational entanglements of people, work, material, processes, and ecologies. It enables understanding with and through the material. Visitors have the possibility to create their own story, a montage in their heads. The biography, thus, does not have a single author but can only be told in multiple variations.

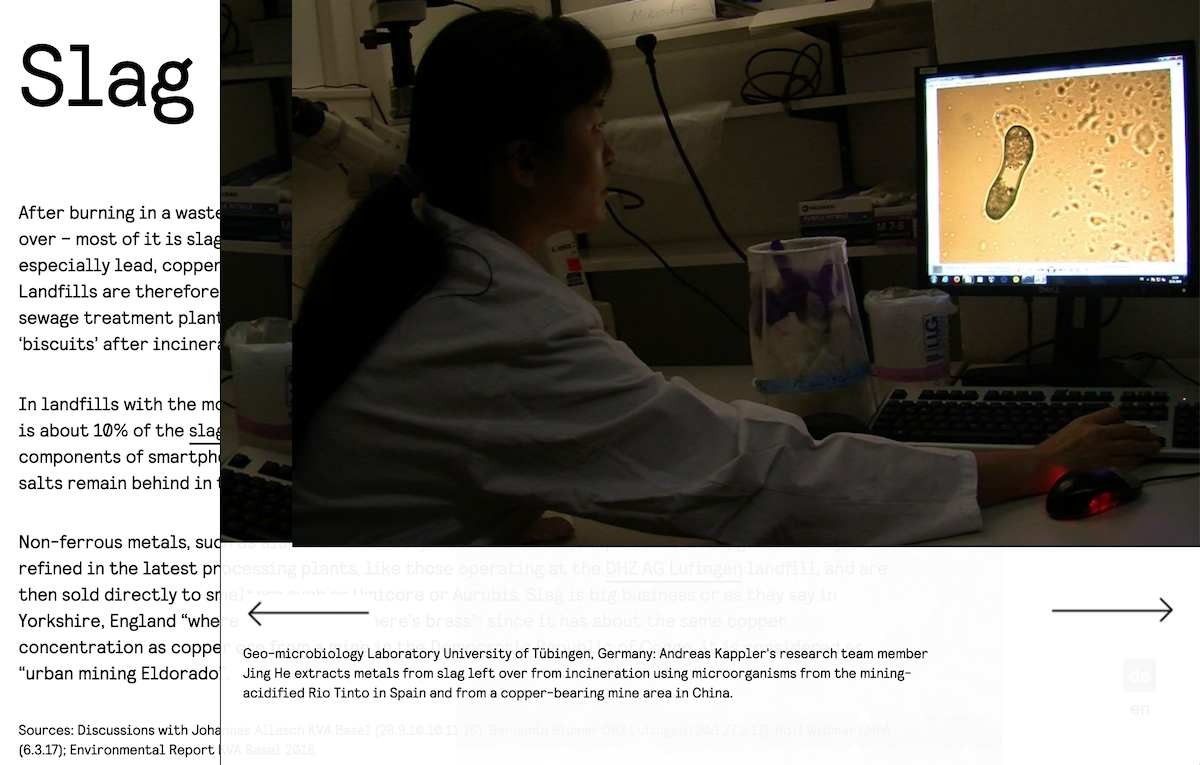

Montage in its expanded understanding supports our intention to make reflections and attitudes towards certain aspects visible by placing contents in relation to each other and in a rather unusual way: The mining of raw materials in Chinese mines appears next to household slag in Swiss landfills and metal extractions from slag left over from waste incineration by a research team in geo-microbiology at the University of Tübingen. Or trading of so-called ‹strategic› metals by Schweizer Metallhandels AG Deutschland creates unexpected ‹entanglements› with mining of cobalt and copper in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Raw materials obtained under health-damaging and ecologically problematic conditions are turned investment material further down the line.

«Traditional colonial practices of control over critical assets, trade routes, natural resources and exploitation of human labor are still deeply embedded in the contemporary supply chains, logistics and assembly lines of digital content, products and infrastructure. In that sense, chains of digital colonialism are made both on the extraction of digital surplus and the traditional exploitation of labor and resources.»12

This «superior form of editing»13 is a reflexive practice of both our intention of relating material and, furthermore, the emerging assemblages in the mind of the recipients: ’Additional’ content is actively created as visitors ‘regroup’ the fragments and units found in the object biography and bring them into a new order.

I always imagined this procedure of a new arrangement of knowledge leading to a self-reflexive moment, establishing a relationship with the material that affects both the recipient and the content: a transformation occurs through active involvement. A non-linear format or an ‘associative’ work as our exhibition – a montage of visual, auditive, textual and material elements within the physical space – can offer the possibility of ongoing new confrontations and linkages of contents. Insofar, I think, the smartphone object biography represents a way of worlding and allows to create possible, new, or other connections and entanglements. Possible-but-not-yet?

«That’s pain. It’s expecting too much when time is out of time, and the waiting that takes place over time opens time to the absence of time – where there is nothing to wait for.»14

Methods are expected to organize research processes in a certain and (by other researchers already) pre-experienced manner. The decision to work with a specific practice is therefore mostly linked to the hope to find some kind of support for what we intend to do.

And after doing, while reflecting the research process: How may limited (and limiting) aspects not only be analysed – and hence ‘justified’ for further research –, but as well be re-jected, de- and re-constructed, re-worked, and research being declared as an open ended work in progress?

At the end of 2015, after one year of project duration, we wrote a text for a publication on artistic e-waste projects, focusing as well on our teamwork. Regarding field work, the following lines are significant: «This intense phase of working in the core team was something very special. We shared what we found during our own investigations, and spent hours in discussion, trying to understand what we were doing. […] Maybe it had to do with the complexity of the subject».15

And – to add now in retrospective – it had to do with what may happen when methods and practices meet the messiness16 and resistance of the encountered (research) realities.

«Believe me, we are never sad enough for the world to be better.»17

On questions of representation and othering; the challenge of finding appropriate strategies and methods

One of the still most innovative methodological concepts of representation which emerged in the wake of the so-called Crisis of Representation or Writing Culture debate18 has been developed by the theorist and filmmaker Trinh T. Minh-ha. Her approach arises from postmodern, feminist, and postcolonial debates within anthropology and is aimed at deconstructing existing paradigms.

«There is no doubt that the act of representation almost always involves violence towards the subject of the representation. There is a real contrast between the violence of the act of representing and the calm within the representation itself.»19

Despite the required transparency, multi-perspectivity or polyphony, the anthropological dilemma of representation cannot be resolved. But it may be defused through differentiated methods of (self-) representation, such as Trinh Minh-ha’s «speaking nearby» instead of «speaking about»20 It is an attempt to enable protagonists to engage in the (cinematic) process with their own ideas and desires concerning self-representation.

The enlarged focus on representation in a more-than-human world deals with the challenge to find adequate practices and formats allowing to include interrelated and entangled stories of different actants and their agential characteristics.

Since working on my licentiate, I have in mind Trinh’s methodological approaches pointing towards a situation where those involved in the process have to deal with concepts of representation and with power structures, but try to do so in a different, more empowering way.

One particular challenge was to deal with the problem of representation inherent in every collaboration, both in terms of content and aesthetics. We approached the concept of post-anthropocene aesthetics primarily by raising questions about how the entanglements of humans and non-humans could be more egalitarian and effective, therefore wondering how research practices could help overcome the representational ‹obstacles› we are facing when dealing with objects or artefacts, and the aesthetical consequences these practices might have in regards to the results of our research.

After visiting the video installation Les entrelacs de l’objet21 by Kader Attia, I wrote down one of his statements: ‹Missing traces› of objects or artefacts in museal collections should be elaborated from the present to the object’s relevant time (e.g. colonial time). As objects move through different contexts parts of their ‘other’ are always included.

«With each step, the world comes to us

With each step, a flower blooms under our feet

Learning / how to walk / anew.»22

‹Doing› is a performative exploration. It is about where, how and with whom research is performed during a process of working (collaboratively) together.

Working together with persons and institutions includes manifold, close or loose, partly complex constellations of knowledge elaboration and exchange. The distinction between ‹scientific› and ‹non-scientific› knowledge becomes irrelevant. More important is the question of how these different forms of knowledge can be consolidated, linked and represented.

‹Doing› takes into account the characteristics of transnational research — its fragments and gaps. Researchers ‹perform the gap›. The performance is characterized by the instability inherent in gaps. The transdisciplinary work at the interface of sciences and arts — the complex work at the borders of science and non-science — contains unstable conditions and unsettling forms of work.

Those conditions, on the other hand, allow insights into how the demarcation of borders is structured, which type of borders (in the joint work) are irritated (and where), which ones are erected elsewhere, and to what extent stabilized or established border relationships might be shifted.24 It is presumably only through the «delimitation of the methodological boundaries» that it is possible to understand the delimitation of ways of life and their techno-medial conditions.25 Delimitation which is understood as a transgression of methods and insights, as a productive entanglement.26

Collaborations with both academic and non-academic experts – project partners, protagonists, audiences, and with technologies – characterizes our transdisciplinary work.

We trace (waste) material and working contexts of people, ranging from local landfills, repair shops, recycling plants or research laboratories to global contexts.

We want to achieve experiential closeness to the material, to its characteristics and fields of interaction. We try to address this aesthetic challenge for instance visually, through the object-oriented close perspective GoPro technology enables.

«What we will say because we must: there is also a photograph of Hirut taken by this Frenchman. A portrait shot while he visited the home of Aster and Kidane and requested a picture of the servants to trade with other photographers or exchange for film. She turns away from it. She does not want to see her picture. She wants to close the box to shut up. But it is here and this younger Hirut also refuses a quiet grave. […]

And when Hirut turns her head so that rays scallop around her like a brilliant flame, what can the eye see but just a young woman seeking comfort in the warmth of an afternoon sun? What does the eye know of her only request: Let me kill the photographer myself. What can the camera see of her later mercy and that lifelong rage?»23

«I am what I am to be not like you» in the song Othering by Naked in English Class27 reverberates.

While observing the everyday work of the protagonists or in conversations with them, we act as ‹accomplices›, even if we do not agree with everything they say. During such moments of involvement, we are interested in the other person's opinion. We approach and try to understand the background of certain actions – it is a process of ‹becoming›. Then, during the analysis and editing of the material, we return to a more distanced and critical role, which could be compared with processes of ‹othering›.

From which position do I intend to speak, do I intend to look?

Stardust we are

the remains

of exploded stars

in the galaxy.

Millions of years of continuous accumulation, accumulation of accumulation.

Millions of year old layers, extracted and mined.

Where and how does the narrative of the life of a smartphone begin?

There is not just one story.

There are only variations and patterns of a life that does not pass away.

Materials that move, transform, shift.

Restless matter, alive, active.

Something always remains behind.

But what exactly?

This is an attempt to tell history from the perspective of matter:

especially of material that lives in the smartphone – neodymium.

A history consisting of certain patterns.

Patterns that sometimes vary.

But how can the story be told when the strands are always severed?32

On the one hand, we visually implement the characteristics and interactions of materiality29 through the media-generated proximity of the GoPro camera technology used, as we think that it may support a «Becoming Waste»30 during reception.

On the other hand, the implementation takes place auditively via an audio essay. We intend a change of perspective by establishing an ‹object-oriented› perspective of the rare earth element neodymium. Through this essayistic procedure, the geo-ecological, technical and socio-economic conditions may be experienced not only cognitively, but also sensually.›

«What you can do best is to constantly locate the place where you stand in every step you make, in everything you record. This way, you can’t objectify the person in front of the camera without being objectified yourself by your own tools. It’s a mutual responsibility.»31

Rethinking one’s own position by inscribing it into the montage process is a form of reflexivity to make the process for the audience transparent, as well as to find an adequate shape for it.

The reflections of the researcher about the relationship with the researched, and the reflections of the researched about their relationship and about oneself is a possibility to represent the meandering positions of the «I».

- Godard, Jean-Luc. Montage, Mon Beau Souci. Cahiers du Cinéma December 1956.

- Puig de la Bellacasa, María. Matters of Care. Speculative Ethics in more than human worlds. University of Minnesota Press 2017a.

- Puig de la Bellacasa, María. Ein Gefüge vernachlässigter Dinge. In: Tobias Bärtsch et al. (Ed.). Ökologien der Sorge. Transversal texts 2017b:137–188.

- Appadurai, Arjun (Ed.). The Social Life of Things. Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge 1986.

- Holm Vohnson, Nina. Labor Days: A Non-Linear Narrative of Development. In: Christian Suhr/Rane Willerslev (Ed). Transcultural Montage. Berghahn Books 2013:131–144 (here 133; 143).

- Suhr, Christian/Willerslev, Rane (Ed). Transcultural Montage. Berghahn Books 2013 (here 12).

- McLean, Stuart. All the Difference in the World. Liminality, Montage, and the Reinvention of Comparative Anthropology. In: Christian Suhr/Rane Willerslev (Ed.). Transcultural Montage. Berghahn Books 2013:58–75 (here 59).

- Marcus, George. Ethnography in/of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography. In: Annual Review of Anthropology 24 1995:95–117.

- Weigel, Moira. Feminist cyborg scholar Donna Haraway: ‘The disorder of our era isn’t necessary’. Interview with Donna Haraway in: The Guardian 24.6.19.

- Barad, Karen. On Touching – The inhuman that therefore I am. (V.1.1). Revision of the article published in differences 23:3, 2012:206–223 and forthcoming for Susanne Witzgall/Kerstin Stakemeier (Ed.). The Politics of Materiality 2014 (here 7).

- Dolphijn, Rick/van der Tuin, Iris (Ed.). Matter feels, converses, suffers, desires, yearns and remembers (Interview mit Karen Barad). In: New Materialism: Interviews & Cartographies. Open Humanities Press 2012:48–70 (here 55; 69). https://quod.lib.umich.edu/o/ohp/11515701.0001.001/1:4.3/--new-materialism-interviews-cartographies?rgn=div2;view=fulltext

- Joler, Vladan. Chains of digital colonialism. In: Ibid. New Extractivism. Assemblage of concepts and allegories. www.extractivism.work 2020.

- As I stated in Coover, Roderick with Pat Badani, Flavia Caviezel, Mark Marino, Nitin Sawhney and William Uricchio. Digital Technologies, Visual Research and the Non-Fiction Image. In: Sarah Pink (Ed.). Advances in Visual Methodology. Sage 2012:191–208 (here 203).

The statement refers to the conceptional framework of the interactive computer installation of Check on Arrival (2004–2006), a research and exhibition project I conducted together with Susanna Kumschick, located at Zurich University of the Arts and funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. - Godard, Jean-Luc. Le Livre d’Image. Casa azul films 2018.

- Caviezel, Flavia/Bürgin, Mirjam/Caminada, Anselm/Demleitner, Adrian/Mertens, Marion/Volkart, Yvonne. Times of Waste. In: Linda Kronman/Andreas Zingerle (Ed.). Behind the Smart World – saving, deleting and resurfacing data. Linz: servus.at 2016:68–79 (here 78).

https://publications.servus.at/2016-Behind_the_Smart_World/html/rttowtow.html - Law, John. After method: Mess in Social Science Research. Routledge 2004.

- Godard, Jean-Luc. Le Livre d’Image. Casa azul films 2018.

- Marcus, George E./Fischer, Michael F. Anthropology as Cultural Critique: An Experimental Moment in the Human Sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1986. / Clifford, James/Marcus, George E. (Ed.). Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press 1986.

- Godard, Jean-Luc. Le Livre d’Image. Casa azul films 2018.

- Minh-ha, Trinh T. Framer Framed. Routledge 1992 (here 96).

- English translation: The entanglements of the object. Exhibition Remembering the Future by Kader Attia at Kunsthaus Zurich, 21.8.–15.11.2020.

- Minh-ha, Trinh T. D-Passage. The Digital Way. Duke University Press 2013 (here 188). Floor text of the large-scale multimedia installation L’Autre marche (The Other Walk) at the Musée du Quai Branly Paris 2006.

- Mengiste, Maaza. The Shadow King. Canongate 2019 (here 7; 424).

- Caviezel, Flavia/Dietsch, Ina/Lustenberger, Brigitte. Arbeiten an den Grenzen. Reflexionen über ein interdisziplinäres Lehr- und Lernprojekt zwischen Kunst und Kulturanthropologie im trinationalen Raum. In: Jacques Picard/Silvy Chakkalakal/Silke Andris (Ed.). Grenzen aus kulturwissenschaftlichen Perspektiven. Panama 2016:134–156 (here 145–146; 153).

- Schönberger, Klaus. Ich sehe was, was du nicht siehst? Ethnographische und künstlerische Forschung im Prozess der Entgrenzung von Wissensformaten. In: Reinhard Johler/Christian Marchetti/Carmen Weith/Bernhard Tschofen (Ed.). Kultur_Kultur. Denken. Forschen. Darstellen. Waxmann: 2013: 272–277. / Leimgruber, Walter. Die Tücken der Entgrenzung. In: Jacques Picard/Silvy Chakkalakal/Silke Andris (Ed.). Grenzen aus kulturwissenschaftlichen Perspektiven. Panama 2016:269–296.

- Schneider, Arnd/Wright, Christopher (Ed.). Between Art and Anthropology: Contemporary Ethnographic Practice. Oxford/New York: Berg 2010.

- Naked in English Class. Othering. Ikarus Records 2017.

- Crawford, Peter Ian. Film as Discourse: The Invention of Anthropological Realities. In: Peter Ian Crawford/David Turton (Ed.). Film as Ethnography. Manchester/New York: Manchester University Press 1992:68–71.

- Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press 2010.

- Dolphijn, Rick/van der Tuin, Iris (Ed.). Matter feels, converses, suffers, desires, yearns and remembers (Interview mit Karen Barad). In: New Materialism: Interviews & Cartographies. Open Humanities Press 2012:48–70 (here 69). https://quod.lib.umich.edu/o/ohp/11515701.0001.001/1:4.3/--new-materialism-interviews-cartographies?rgn=div2;view=fulltext

- Minh-ha, Trinh T. Cinema Interval. Routledge 1999 (here 72).

- Intro to the audio essay Smartphone Object Biography/Neodymium by research team Times of Waste. Listen to the sound essay by scrolling down on https://objektbiografie.times-of-waste.ch/en/mining/.